Input Validation for Security

Filed under: Development, Security

Validating input is an important step for reducing risk to our applications. It might not eliminate the risk, and for that reason we should consider what exactly we are doing with input validation.

Should you be looking for every attack possible?

Should you create a list of every known malicious payload?

When you think about input validation are you focusing on things like Cross-site Scripting, SQL Injection, or XXE, just to name a few? How feasible is it to attempt to block all these different vulnerabilities with input validation? Are each of these even a concern for your application?

I think that input validation is important. I think it can help reduce the ability for many of these vulnerabilities. I also think that our expectation should be aligned with what we can be doing with input validation. We shouldn’t overlook these vulnerabilities, but instead realize appropriate limitations. All of these vulnerabilities have a counterpart, such as escaping, output encoding, parser configurations, etc. that will complete the appropriate mitigation.

If we can’t, or shouldn’t, block all vulnerabilities with input validation, what should we focus on?

Start with focusing on what is acceptable data. It might be counter-intuitive, but malicious data could be acceptable data from a data requirements statement. We define our acceptable data with specific constraints. These typically fall under the following categories:

* Range – What are the bounds of the data? ex. Age can only be between 0 and 150.

* Type – What type of data is it? Integer, Datetime, String.

* Length – How many characters should be allow?

* Format – Is there a specific format? Ie. SSN or Account Number

As noted, these are not specifically targeting any vulnerability. They are narrowing the capabilities. If you verify that a value is an Integer, it is hard to get typical injection exploits. This is similar to custom format requirements. Limiting the length also restricts malicious payloads. A state abbreviation field with a length of 2 is much more difficult to exploit.

The most difficult type is the string. Here you may have more complexity and depending on your purpose, might actually have more specific attacks you might look for. Maybe you allow some HTML or markup in the field. In that case, you may have more advanced input validation to remove malicious HTML or events.

There is nothing wrong with using libraries that will help look for malicious attack payloads during your input validation. However, the point here is to not spend so much time focusing on blocking EVERYTHING when that is not necessary to get the product moving forward. Understand the limitation of that input validation and ensure that the complimenting controls like output encoding are properly engaged where they need to be.

The final point I want to make on input validation is where it should happen. There are two options: on the client, or on the server. Client validation is used for immediate feedback to the user, but it should never be used for security.

It is too easy to bypass client-side validation routines, so all validation should also be checked on the server. The user doesn’t have the ability to bypass controls once the data is on the server. Be careful with how you try to validate things on the client directly.

Like anything we do with security, understand the context and reasoning behind the control. Don’t get so caught up in trying to block every single attack that you never release. There is a good chance something will get through your input validation. That is why it is important to have other controls in place at the point of impact. Input validation limits the amount of bad traffic that can get to the important functions, but the functions still may need to do additional processes to be truly secure.

SameSite By Default in 2020?

Filed under: Development, Security, Testing

If you haven’t seen, Cross Site Request Forgery (CSRF) is getting a big protection by default in 2020. Currently, most protections need to be implemented explicitly. While we are seeing some nonces included and checked by default (Razor Pages), you typically still need to explicitly check the nonce. This requires that the developers understand that CSRF is a risk and how to prevent it. They then need to implement a mitigating solution.

Background

CSRF has been around for a long time. For those that don’t know, it is a vulnerability that allows an attacker to forge requests to your application that the user doesn’t initiate. Imagine being able to get a user to transfer money using a request like https://yourbank.com/transfer/300. They place this request on another site in an image tag. When the image attempts to load, it sends the request to the other bank site. Assuming the bank site uses cookies for authentication and session management, these cookies are sent with the request and the transfer is made (if the user was logged into their bank account).

The most common mitigation was to include a nonce with each request. This made the request to transfer money unique for every user. This is effective, but does require that the developer add the nonce and validate it on the request. A few years back, the browsers started adding support for the samesite attribute. This has the advantage of being set on the cookies instead of every request. The idea behind samesite is that a cookie will not be sent if the requesting domain is different than the destination domain. In our example above, if mybank.com has an image tag set to yourbank.com, the browser will not send the cookies for yourbank.com with the request.

Today

Fortunately, we are at a time when most browsers have support for samesite, but it does require that the developer set the appropriate setting. Like implementing a nonce, this is put on the developer to take an explicit action. The adoption of samesite is gaining. Frameworks like .Net Core set this for identity cookies to lax by default.

2020

Chrome has announced that in 2020, Chrome 80 will set the samesite flag to lax for all cookies by default. (https://blog.chromium.org/2019/10/developers-get-ready-for-new.html) This is good news, as it will help take a huge dent out of cross-site request forgery. Of course, that only means if you are using Chrome as a browser. I am sure that Mozilla and Microsoft will follow suit, but there is no mention of a timeline to when that will happen. So is CSRF dead, no. It has taken a strong blow though.

But wait, it is just set to lax.. what does that mean? There are two settings for samesite: strict and lax. Lax, as its name implies is a little more forgiving. For the most part, it is good enough coverage if you follow your basic guidelines (Don’t use GET for making changes to your system). However, if you do use GET requests, you still have a risk. Remember that example earlier https://yourbank.com/transfer/300? This is using a GET request. with Lax, an attacker can put that link in a link tag on their site, rather than an image tag. Now, if the user clicks the link, it will open it as the top level request and will still send the cookies. This is that difference between strict and lax. Strict would not allow the cookies to be sent in this scenario.

What does this mean?

At this point, this change means you should be checking your current applications to see if you have any type of cross-site requests that need to send cookies to work. If these exist, you will need to take action to turn samesite off or make other accommodations. If you find that samesite will be a problem for your setup, you can turn it off by setting samesite: none. This does require that the cookie is set to secure.

If your application doesn’t use cross-site requests, you still should take action. Remember, this only defaults in Chrome. So if your users are using anything else, this change doesn’t effect them yet. They will still be vulnerable if you are not implementing other CSRF mitigations.

Making the Change in FireFox Now

FireFox does have the ability to enable this behavior in the about:config. Starting in FireFox 69, you can modify the following preferences:

- network.cookie.sameSite.laxByDefault

- network.cookie.sameSite.noneRequiresSecure

These are both set to false by default, but a user can change them to true. Note that this is a user setting and not one that you can force your users to set. It is still recommended to set the samesite attribute through your application.

Making the Change in Chrome Now

Chrome has the ability to enable this behavior in chrome://flags. There are two settings:

- SameSite by default cookies

- Cookies without SameSite must be secure

These are currently both set false by default, but you can change them too true.

Be Careful

As a user, making these changes can add a layer of protection, but it can also break some sites you may use. Be careful when enabling these since it may render some sites unreliable.

Intro to npm-audit

Our applications rely more and more on external packages to enable quick deployment and ease of development. While these packages help reduce the code we have to write ourselves, it still may present risk to our application.

If you are building Nodejs applications, you are probably using npm to manage your packages. For those that don’t know, npm is the node package manager. It is a direct source to quickly include functionality within your application. For example, say you want to hash your user passwords using bcrypt. To do that, you would grab a bcrypt package from npm. The following is just one of the bcrypt packages available:

https://www.npmjs.com/package/bcrypt

Each package we may use may also rely on other packages. This creates a fairly complex dependency graph of code used within your application you have no part in writing.

Tracking vulnerable components

It can be fairly difficult to identify issues related to these packages, never mind their sub packages. We all can’t run our own static analysis on each package we use, so identifying new vulnerabilities is not very easy. However, there are many tools that work to help identify known vulnerabilities in these packages.

When a vulnerability is publicly disclosed it receives an identifier (CVE). The vulnerability is tracked at https://cve.mitre.org/ and you can search these to identify what packages have known vulnerabilities. Manually searching all of your components doesn’t seem like the best approach.

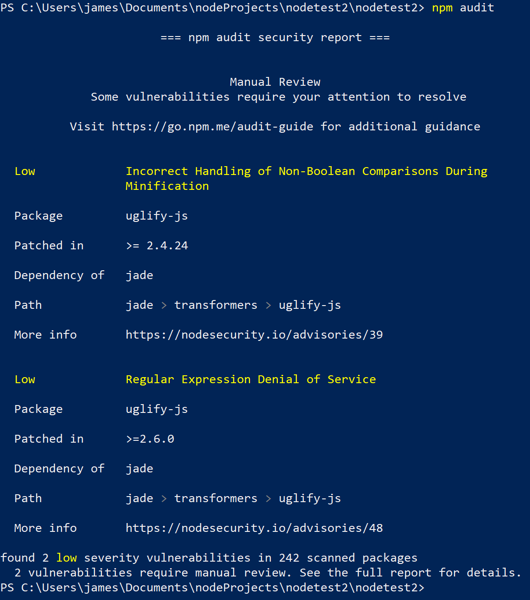

Fortunately, npm actually has a module for doing just this. It is npm-audit. The package was included starting with npm 6.0. If you are using an earlier version of npm, you will not find it.

To use this module, you just need to be in your application directory (the same place you would do npm start) and just run:

npm audit.

On the surface, it is that simple. You can see the output of me running this on a small project I did below:

As you can see, it produces a report of any packages that may have known vulnerabilities. It also includes a few details about what that issue is.

To make this even better, some of the vulnerabilities found may actually be fixed automatically. If that is available, you can just run:

npm audit fix.

The full details of the different parameters can be found on the npm-audit page at https://docs.npmjs.com/cli/audit.

If you are doing node development or looking to automate identifying these types of issues, npm-audit may be worth a look. The more we can automate the better. Having something simple like this to quickly identify issues is invaluable. Remember, just because a component may be flagged as having a vulnerability, it doesn’t mean you are using that code or that your app is guaranteed vulnerable. Take the effort to determine the risk level for your application and organization. Of course, we should strive to be on the latest versions to avoid vulnerabilities, but we know reality diverts from what we wish for.

Have you been using npm-audit? Let me know. I am interested in your stories of success or failure to learn how others implement these things.

JavaScript in an HREF or SRC Attribute

Filed under: Development, Security, Testing

The anchor (<a>) HTML tag is commonly used to provide a clickable link for a user to navigate to another page. Did you know it is also possible to set the HREF attribute to execute JavaScript. A common technique is to use the onclick event of the anchor tab to execute a JavaScript method when the user clicks the link. However, to stop the browser from actually redirecting the HREF can be set to javascript:void(0);. This cancels the HREF functionality and allows the JavaScript from the onclick to execute as expected.

In the above example, notice that the HREF is set with a value starting with “javascript:”. This identifier tells the browser to execute the code following that prefix. For those that are security savvy, you might be thinking about cross-site scripting when you hear about executing JavaScript within the browser. For those of you that are new to security, cross-site scripting refers to the ability for an attacker to execute unintended JavaScript in the context of your application (https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Cross-site_Scripting_(XSS)).

I want to walk through a simple scenario of where this could be abused. In this scenario, the application will attempt to track the page the user came from to set up where the Cancel button will redirect to. Imagine you have a list page that allows you to view details of a specific item. When you click the item it takes you to that item page and passes a BackUrl in the query string. So the link may look like:

https://jardinesoftware.com/item.php?backUrl=/items.php

On the page, there is a hyperlink created that sets the HREF to the backUrl property, like below:

<a href=”<?php echo $_GET[“backUrl”];?>”>Back</a>

When the page executes as expected you should get an output like this:

<a href=”/items.php”>Back</a>

There is a big problem though. The application is not performing any type of output encoding to protect against cross-site scripting. If we instead pass in backUrl=”%20onclick=”alert(10); we will get the following output:

<a href=”” onclick=”alert(10);“>Back</a>

In the instance above, we have successfully inserted the onclick event by breaking out of the HREF attribute. The bold section identifies the malicious string we added. When this link is clicked it will prompt an alert box with the number 10.

To remedy this, we could (or typically) use output encoding to block the escape from the HREF attribute. For example, if we can escape the double quotes (” -> " then we cannot get out of the HREF attribute. We can do this (in PHP as an example) using htmlentities() like this:

<a href=”<?php echo htmlentities($_GET[“backUrl”],ENT_QUOTES);?>”>Back</a>

When the value is rendered the quotes will be escapes like the following:

<a href=”" onclick=&"alert(10);“>Back</a>

Notice in this example, the HREF actually has the entire input (in bold), rather than an onclick event actually being added. When the user clicks the link it will try to go to https://www.developsec.com/” onclick=”alert(10); rather than execute the JavaScript.

But Wait… JavaScript

It looks like we have solved the XSS problem, but there is a piece still missing. Remember at the beginning of the post how we mentioned the HREF supports the javascript: prefix? That will allow us to bypass the current encodings we have performed. This is because with using the javascript: prefix, we are not trying to break out of the HREF attribute. We don’t need to break out of the double quotes to create another attribute. This time we will set backUrl=javascript:alert(11); and we can see how it looks in the response:

<a href=”javascript:alert(11);“>Back</a>

When the user clicks on the link, the alert will trigger and display on the page. We have successfully bypassed the XSS protection initially put in place.

Mitigating the Issue

There are a few steps we can take to mitigate this issue. Each has its pros and many can be used in conjunction with each other. Pick the options that work best for your environment.

- URL Encoding – Since the HREF is meant to be a URL, you could perform URL encoding. URL encoding will render the javascript benign in the above instances because the colon (:) will get encoded. You should be using URL encoding for URLs anyway, right?

- Implement Content Security Policy (CSP) – CSP can help limit the ability for inline scripts to be executed. In this case, it is an inline script so something as simple as ‘Content-Security-Policy:default-src ‘self’ could be sufficient. Of course, implementing CSP requires research and great care to get it right for your application.

- Validate the URL – It is a good idea to validate that the URL used is well formed and pointing to a relative path. If the system is unable to parse the URL then it should not be used and a default back URL can be substituted.

- URL White Listing – Creating a white list of valid URLs for the back link can be effective at limiting what input is used by the end user. This can cut down on the values that are actually returned blocking any malicious scripts.

- Remove javascript: – This really isn’t recommended as different encodings can make it difficult to effectively remove the string. The other techniques listed above are much more effective.

The above list is not exhaustive, but does give an idea of ways to help reduce the risk of JavaScript within the HREF attribute of a hyper link.

Iframe SRC

It is important to note that this situation also applies to the IFRAME SRC attribute. it is possible to set the SRC of an IFRAME using the javascript: notation. In doing so, the javascript executes when the page is loaded.

Wrap Up

When developing applications, make sure you take this use case into consideration if you are taking URLs from user supplied input and setting that in an anchor tag or IFrame SRC.

If you are responsible for testing applications, take note when you identify URLs in the parameters. Investigate where that data is used. If you see it is used in an anchor tag, look to see if it is possible to insert JavaScript in this manner.

For those performing static analysis or code review, look for areas where the HREF or SRC attributes are set with untrusted data and make sure proper encoding has been applied. This is less of a concern if the base path of the URL has been hard-coded and the untrusted input only makes up parameters of the URL. These should still be properly encoded.